Ben Dalton: 'Your PhD, Your Brain, and Your B-Movies'

Your brain – big, buxom, full of neurons, and a pineal gland, and an amygdala, and a basal ganglia, and then some – is what is doing your PhD. It reads your stuff, it writes your stuff, and it decides which Sainsbury’s korma to microwave whilst you email your supervisor to postpone your stuff.

“Everyone has a hidden emotional motive behind their PhD,” my friend always says, “what is yours?” Day to day, I write about connections between contemporary French philosophy, cinema and neuroscience, so I like to think that I was always aware of the brain. Since undergoing an out-of-the-blue Endoscopic Third Ventriculostomy this Christmas due to a rogue blockage in one of my brain’s water tanks, however, I could not be more aware of it.

I have realised more than ever that I owe it to my brain to figure out who it is and what it does. So as well as using it to think about other brain-workings in French philosophy and cinema, I have decided to get to know my own much better. I have decided that I’m going to treat this throbbing alien in my skull with the respect it deserves – like the true Genovian princess it really is – and that this journey might as well be a voluptuous, bawdy experience, and needn’t necessarily start with the MRI scanner.

An unforeseen delight which has emmerged from my research – between libraries and hospitals and cinemas – has been the brain B-Movie. B for Brain, if you can stomach that degree of tweeness. Whatever your own reason for wanting to explore the brain writing your PhD, here are three gloriously campy places to start:

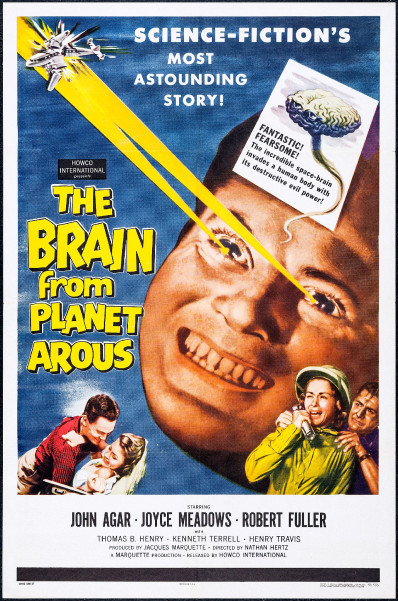

The Brain from Planet Arous

This 1957 favourite, directed by Nathan H. Juran, does exactly what it says on the tin. A brain-shaped alien by the name of Gor descends to earth and takes over the body of a young scientist, using his powers to destroy the planet bit by bit. Meanwhile, another of the brain-shaped race also descends to earth, explaining that Gor is a wanted terrorist on their own planet. It is found that Gor’s weak spot is his Fissure of Rolando, or the central sulcus: a line that separates the parietal lobe from the frontal lobe in the brain.

The primal anxiety that we cannot control our own brains parts from the logic that ‘we’ are something different to the alien jellies that somehow serve as a material tether. At once uncannily the most intimate and most alien part of ourselves, the inkling that our decisions, drives and freedoms are the result of something prior to the illusion of our autonomous consciousness is haunting. Also a great way to discover the word sulcus.

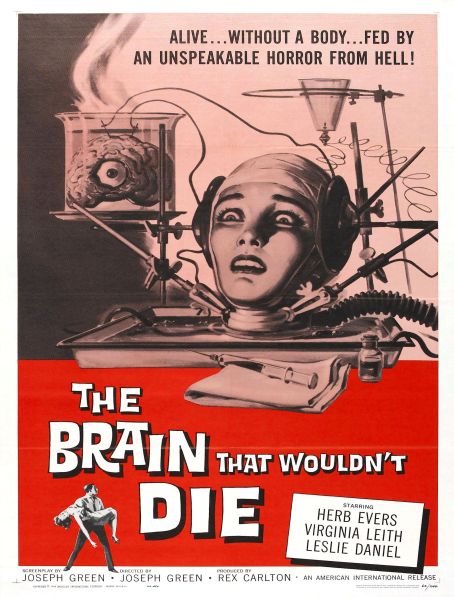

The Brain That Wouldn’t Die

Joseph Green’s minor 1962 masterpiece follows unhinged surgeon Dr Cortner as he prepares to attempt the world’s first head transplant. Following a road accident in which his fiancée Jan is decapitated, Cortner fights to keep her head alive on a wet tray in his basement. Jan, coming back to consciousness on the tray, is horrified at her new immobile state, begging to die. Cortner looks for a new body for his wife’s head, frequenting strip bars and modelling contests for a suitable match. Back in the basement, however, Jan plots revenge, communicating telepathically with a monster Cortner is keeping in his cupboard.

The Brain That Wouldn’t Die is a savage exploration of the claustrophobia of being stuck inside a head or stuck within a brain. In a culture of hyper disposability and flexibility, the idea that there might be elements of ourselves that are limited, finite and unfixable is a true horror. If this film is chilling, it is maybe not because it is about a brain transplant, but because this brain transplant isn’t yet fully possible.

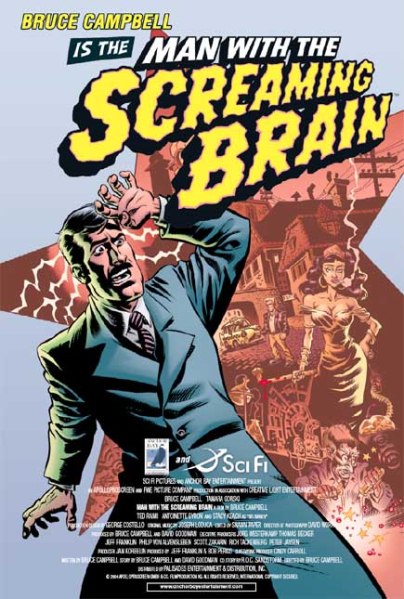

Man with the Screaming Brain

After two men are killed by the same woman, a crazy scientist brings them back to life by transplanting the healthy half of the first victim’s brain into the head of the second victim, of which half the brain has also been damaged. Brought to life is a horrifying composite of both victims, with half of both men’s memories alive within the same head. These combined consciousnesses work together to track down their killer.

This is a film about fragments and divisions, both within a singular consciousness and between different brains. Here explored is a self that is nothing but the illusory unity of many disparate drives and neural mechanisms in a singular skull, and this within a world of countless separate, competing selves. The hive mind is both headache of conflictions and the illusory promise of a unified origin.

Whilst if you want brains from your music you have to go metal – the broken or eternal hearts of Dion and Houston become the scrambled or undead brains of Metallica – if you want real cerebrum from your cinema, these darker low budget recesses might just be your boy. I’m always open to suggestions for more B Movies, so help me out below if you’ve come across any particularly brilliant examples.

Ben Dalton is a first year PhD candidate at King’s College London. His research looks at conceptions of (neuro)plasticity and metamorphosis within contemporary French philosophy, neuroscience and cine