Edward Wren: 'A Tangential View of History'

I can see that it has its problems, but I think that the metaphor of a tangent has something compellingly to do with the interpretation of history. The term “tangent” unavoidably means a straight line in space, at least when we think of it in its geometric sense. That fact by itself will probably not endear it to historians looking to reflect on their own practice. A linear history is likely an evolutionary history, a teleological one. It might imply that historical process straightforwardly means historical progress, which is unpalatable to many.

But it need not be this way. It is fair to say that a linear history can mean something more minimal – that human subjects can only move forward through their lives, one day at a time, and that they can always reimagine the past, but never change it. This might seem like a truism, but at the end of Milan Kundera’s The Unbearable Lightness of Being (1984), the philosophical narrator put it brilliantly:

‘Human time does not turn in a circle; it runs ahead in a straight line. That is why man cannot be happy: happiness is longing for repetition.’

Given the importance of the concept of “lived experience”, especially for social historians of the past decades, I find Kundera’s straight line a beautifully stark way of describing the contingency and frailty of human life.

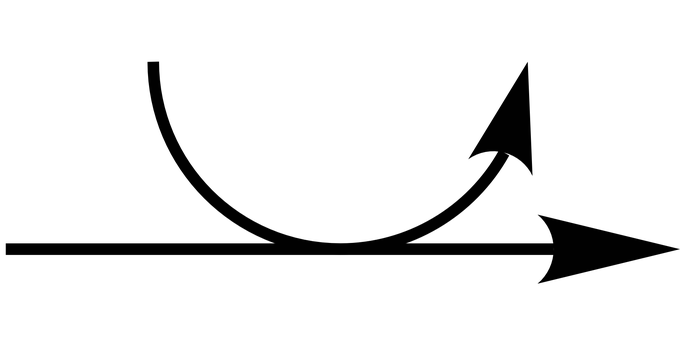

And so far I have merely touched on the tangent metaphor. A tangent only exists in relation to a curve; a given line can be drawn for any of the curve’s infinite number of points. When historians write accounts of the past, they have to chart some chronology that indeed “touches” on real events, but in doing so they will be led on a journey of their own – they will search archives, make notes, argue with editors, present their findings to peers. They will also have to decide what point on the “curve” of past events constitutes their point of departure. And though they will defend their choice, perhaps to an audience wary about another book on the Reformation (for example), they might also recognise its degree of arbitrariness, or at least its relativity to their own intended programme of research.

These are reasons why I find the tangent metaphor appealing. As a graduate student working on Adam Smith’s intellectual formation in eighteenth-century Glasgow, my instinct is not to think about his writings on ethics and jurisprudence as an improvement upon those of his predecessors. Rather, I am trying to understand how Smith used an inherited tradition of moral philosophy as his point of departure for his own innovative study, which incorporated knowledge of vernacular literature and systems of positive law. Though my research is very much a work in progress, I am starting to think that Smith, too, found himself going off on a tangent.

Edward Wren is a first-year History PhD student at the University of Cambridge. He is interested in the history of philosophy and the social sciences in northwest Europe from the eighteenth century to the present day.