Imogen Cassels: 'You met me at a very strange time in my life'

You met me at a very strange time in my life

It’s a line from a film I haven’t seen of a book I don’t like, a quasi-aphoristic phrase both throwaway and faux-deep, which was thrown up again and again on the internet when I was a teenager. This is the last line of Fight Club (1999), spoken by Edward Norton’s character to Helena Bonham Carter’s character. They are standing high up in a building in a city, one with floor-to-ceiling glass; they are holding hands; they are wearing blocky clothes which partially obscure their bodies, then cut off sharply at the knees, so knocking these sexy movie stars out of proportion, and making them somehow also schoolchildren. Their silhouettes are matchy-matchy like their beautiful faces. And as all this goes on, the city they are watching falls into fiery collapse and skyscrapers very like the one they are standing in violently re-stack into themselves and bomb. The background these dark figures stand against is blue. A guitar solo comes in.

There is no way, then, that me using this line on you can feel real. It’s far too general, slick, or familiar—but it is, I wonder, true. This last year has often felt unreal to me, anyway. Generic, the line is an easy fit, its monosyllables are so childlike and so full of blackly comic understatement as to make it easy to reach for, even slippery. Well, slippery, you might say—that is just what words are like. Clive Scott writes of how

A poem is a garment both tailor-made (reading it is like a series of fittings) and off the peg (other people wear it and it looks different on them) […] What we need as readers of poems is a reason for reading the same thing over and over again with renewed and undiminished benefit to ourselves; and we can only have that if we neither know ourselves nor the poem, the latter being a natural consequence of the former […]

I can’t make Scott’s tailor-made account of the experience of reading poetry fit this concerning phrase exactly—his focus, after all, is prosodic—but it covers some of the body’s ground. Where Scott might articulate how the perception of a poem’s prosody changes with reading, and the repetition of its sound forms strata and diversifies sense, the effects of repeating this line—You met me at a very strange time in my life—are far more basic, as each word sheds and regains old and new personal referents. That is, sometimes I will mean you, sometimes /you/, sometimes YOU, and You, and you. You, too. So, ‘other people wear it and it looks different on them’, and Fight Club’s line has been adopted, co-opted, misquoted, and appropriated by many, but on each one of us (that is, also on me), it can be tailored to fit, according to how we choose to fill its blanks. But Scott’s observation is more incisive than it is comfortable, for all that it is radically inclusive; we can only have this ‘if we neither know ourselves nor the poem, the latter being a natural consequence of the former’. So, what might ‘me’ mean as a referent during a period of intense or traumatic change? It feels as if there is no such thing as ‘me’. Sometimes this experience of compromised self is pleasurable (as Fight Club might well imply); it is, as Scott suggests, bound up with the experience of reading a poem or book, and losing oneself to others’ rhythms. It is often desirable. It makes meeting people strange.

Six weeks after my mother died I went back to university to begin a nine-month masters. I have done it. In a week it will be the first anniversary of her death and I already have little idea of how the last year has happened at all, let at all happened (as it did) quite well. Among the recollections I do have are unsettling flashes of myself watching myself in something like what John Berger describes in his Ways of Seeing (1972):

A woman must continually watch herself. She is almost continually accompanied by her own image of her herself. Whilst she is walking across a room or whilst she is weeping at the death of her father [mother], she can scarcely avoid envisaging herself walking or weeping.

Walking through a department store there is a sudden flash of something breaking through, a sense of a forcefield of new hardness holding me up, a vague perception of the effort of sustaining this façade of togetherness, like a meniscus that would like to break. But, then, I had read Berger’s essay years before my mother died; wouldn’t I naturally adopt the self-description I was already familiar with? It does not come naturally to look rested, to work hard and pass it off as nothing, to scrape what clean clothes you have on your bedroom floor into an outfit that says sleek or easy (like the slick parting-shot of Fight Club which fits all but suits none). None of these sentiments are new to anyone, but I find them redoubled with a kind of hyper-water-tension. This charm of polishedness puts off the fact that my mother died, or is dead; grief does not get to go to the pub; grief can’t follow me to the bright coffee shop; grief folds under a stack of books and waits its turn, which never comes. Working copes. I am not about to dissolve in your local shop, I only want you to know that I no longer have a world to live in that quite coheres.

You met me at a very strange time in my life: this year I have met lots of new people. There have been so many people to exchange love with, to knot up bodily instinct with, and who have given me love back in kind. And I want to yell at them some warning that the me they have met now is not the me they would have met two, six, nine months ago; that I am not sure who this person is, how long she’ll last. This year, for instance, I have learned to dress better, to the extent that I find its new chic unnerving or fake; I am puzzled and wary of this rather than outright scared, but this sense of unease is only soon another form of exhaustion. I wear more skins, fur, leather and shearling, because it is like keeping myself within another’s casing so I do not fall out or apart; it keeps out cold and/or grief; pronouncing its glamour as distraction; it is beauty and warmth at the price of pain and suffering, worn as external sign. Hello.

There is a poem by Frank O’Hara that I have known for a long time called ‘Mayakovsky’. It opens like this:

My heart’s aflutter!

I am standing in the bath tub

crying. Mother, mother

who am I? If he

will just come back once

and kiss me on the face

his coarse hair brush

my temple, it’s throbbing!

then I can put on my clothes

I guess, and walk the streets.

And ends like this:

Now I am quietly waiting for

the catastrophe of my personality

to seem beautiful again,

and interesting, and modern.

[…]

It may be the coldest day of

the year, what does he think of

that? I mean, what do I? And if I do,

perhaps I am myself again.

‘Mayakovsky’ might itself be something of a delayed grief-poem, or poem-in-tribute (Vladimir Mayakovsky died in 1930), but the poem is also, more interestingly, a disparate body assembled, a garment re-tailored: Andrew Epstein notes James Schuyler’s recollection that ‘the poem only came about because [Schuyler] found two poems that O’Hara had forgotten about folded in a book, and suggested he splice them together with two other short poems to create a four-part work’. O’Hara’s is a poem which might not otherwise have quite happened in the form we now know it; it is also a poem about not knowing what ‘I’ is, which itself does not recognise a single ‘I’. It’s also one of several poems which changed, alchemically, for me, after my mother died. I cannot go back to read it in the way I did beforehand. ‘Mayakovsky’ is a poem cannibalised and reconstituted, a body which does not seem to immediately recognise itself, even as it watches itself crossing a room [stanza], or weeping—‘then I can put on my clothes / I guess, and walk the streets’. Its speaker advances in hopefulness only to trip into anxiety and tears again: the poem’s select joys (of being ‘myself again’) are counterbalanced with a difficulty that persists: it ‘may be the coldest day of / the year’. In love, we naturally mix ‘you’ and ‘I’ up, in entangled forms or futures: I cannot imagine a life without you, I do not want to have to, but how can we bind ourselves when one of us (‘I’) has lost a known fixed shape? Mother mother who am I. You who are not here.

In a seminar with Andrea Brady and John Wilkinson, we spoke about moments of shooting affect in poems, where a clump of lines arrests or cuts you out of something; a garment suddenly tightening on you. These are not only moments of recognition, but actually surprise, often planted with the gravity of a line-break. These poetic elements frequently resemble the solid punchline of a joke, which derives its spring sometimes from pure shock, but more often from the sudden revelation of a previously-hidden inevitability. So in poems we see ourselves, maybe, but always reflected or refracted strangely, or where least expected. An image transformed in miniature or upside-down. ‘I am standing in the bath tub / crying. Mother, mother / who am I?’ surprises with its sudden long-legged enjambment, stripping away whatever you might have put on this morning to ward off bad incident, and leaving you vulnerable to O’Hara’s carefully-plotted love. In ‘Mother, mother’ there is ‘other, other’, an echo which hangs over ‘I’; if you take out O’Hara’s punctuation you have the three words ‘I if he’: if x, y; if you, me. Or, in grief, if not-you, (not-)me. Without really telling you, grief opens up your constructedness-by-others. You met me at a very strange time in my life, and so now you make me up, and I still don’t know who either of us are. I keep my clothes alternately close-fitting and too loose, to leave room and cleave to what I have. You met me at a very strange time in my life; I’m glad, at least, you did.

1st August, 2018

Post-script, August 2019

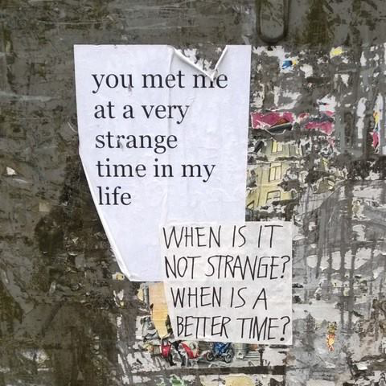

It’s a little over a year later. I’ve not known particularly what to do with the above piece of writing, not least for its faults—somewhat forced, more than a little self-indulgent, moving too quickly between its constituent points to do them proper justice—and the fact that it (perhaps understandably) doesn’t know what it is. Part personal essay, part cursory nod to lit. crit., mostly confessional. It is, if nothing else, an interesting window into my head twelve months ago; and, I remind myself, it’s okay not to cohere. Most of all, however, this writing is uneasy because it wants less to be a general reflection and more a direct address: I want to tell you this. Maybe I should have just messaged my friends to tell them, or brought it up in conversation; it’s a mark of trust and love, however, that I know they would have brushed my worry aside with some variation on I love you anyway, new you or no. Putting it in something like an essay, then (and in the full sense of that word), I can make my address stylised enough to set. Whatever. I came back here because, a few weeks ago, I found something on the internet, again:

I like lots of things about this; the sharp ridiculing of Fight Club’s cliché for what it is, in shouty, slanty capitals, but like it most of all for what it has to say—that life is always strange or estranging. ‘WHEN IS A BETTER TIME?’, this canny respondent asks, in a parody of tactful attempts to arrange a meeting: when would be a better time for your mother to die? Thursday, p.m.? The usual place? It’s not necessarily that Fight Club’s one-liner is false (I stand by it, still, in many ways) but that this sequel to it opens up far more accurate or diverting reflections. For example: the year after the year after my mother’s death has been strange, too. People I met during my master’s have moved away, many back to America—where I send them flirtatious emails telling them to return and do their PhDs in the UK, with me, where they belong. So as it was strange with them it’s strange again newly without: I go to the haunts we occupied like you might revisit a tomb; as spring and summer come round, I’m jolted walking across a place by the memory of a happiness that refuses to repeat itself. Maybe every year after a death is strange; maybe that’s not really strange at all.

There’s a good album by The Weepies called Say I Am You, which came out in 2006. I spent most of last summer listening to it, lying in bed, interspersed with Stacey Kent when the afternoon got too hot. I’ve spent a good deal of this summer listening to Say I Am You, too. In fact, I’m listening to it now. It’s an album mostly of love songs and despair, but the easy proposition of the title is what gets me most (a kind of x if y again)—the way it centres profound affection for other people as a form of bodily, mystical, personal exchange, a sacrifice which is also a consumption. It’s that vertigo, again, of getting lost; of being so happy and comfortable with others I forget to watch myself or notice my own body. It’s a bliss that just happens, you can’t recreate it. It’s bodily mostly because it gets you out of your body. That’s a good thing. Reflecting on his early years, the part-time British surrealist and full-time eccentric Philip O’Connor writes of how, when his mother left him as a young child, it fucked up his sense of touch, or the perceived boundaries of his body. Here:

Mother told me she must leave me but would return very soon. But she stayed away for two years […] I remembered the feel of her hands like living leaves on me so that when others touched me, the association aroused immediately an excruciating hope and a baleful disappointment that developed into a neurasthenic noli me tangere. My skin developed a frantic intelligence of contact that short-circuited satisfaction from any contact, the hope being frightened out of existence by the sharp memory that this was not the one, the real thing […]

Skin is intelligent—when you are a child and your mother leaves you have to find a way of existing in the world that does not hurt you. O’Connor’s noli me tangere is a defence mechanism predicated against hope; in my case, these mechanisms mostly take the form of clothes. They make you into a different shape, they provide a form of control over where and how others can touch you. And it’s not, of course, that any new person I meet and like becomes a replacement for my mother, but that each person becomes an apparently much-needed way for me to try and re-establish the world, in a utopia where I am surrounded by those I love, and who will never leave me like she had to. Bodies, like words, want respondents (‘WHEN IS IT NOT STRANGE? WHEN IS A BETTER TIME?’), contact or touch; whether through new association or a resemblance of place which prompts memories you couldn’t otherwise get back to; like O’Connor, I am sensitive to the electricity only a certain kind of touch can instil, in an act of love or poetic fission. I want company to make me feel like I am somewhere I am otherwise not, when the world I live in is not in the order I asked of it. But, I can hear my mother saying, Life is short and You get what you’re given. And ‘WHEN IS IT NOT STRANGE? WHEN IS A BETTER TIME?’ makes me smile, and that is enough.

The excerpts from Frank O'Hara can be found in 'Mayakovsky', Selected Poems, ed. Donald Allen (Manchester: Carcanet, 2005).

Imogen Cassels is a PhD candidate at the University of Cambridge. She is the author of Arcades (Sad, 2018) and Mother; beautiful things (Face, 2018). Her poems have appeared in the London Review of Books, the White Review, the Cambridge Literary Review, Blackbox Manifold, Hotel, and elsewhere.