Mathilda Oosthuizen: 'Ersilia: Excavating the (In)visibility of Objects'

In the town Ersilia, the inhabitants mark out social connections with coloured strings that remain after the residents have left. A micro-story from Invisible Cities by Italo Calvino – it was these strings that first tied together the name and the archaeological dig.

A site where objects, artefacts, are lifted from the ground, into visibility and given meaning; an action that suggests that whilst they were enfolded, consumed, entombed in the ground they had no meaning. Judith Butler, in Bodies That Matter posits that ’identifications belong to the imaginary,’[i] in which case the strings, the object, the ground from which it is extracted, are not so easily distinguishable.

These strings trace the linear way in which we categorise, separate and label – isolate – the nonhuman from the human. The borders upon which we base who is what and what is who.

Come this way. Only through the trees can you see the tenebrous sky. This is particularly true now; multiple criss-crossings of indistinguishable shapes and blank greyness intercept spindly lopsided rectangles of more blank greyness.

The hovering strings[ii]. The visual identifiers, marking out one area from the other– dividing the digging– suspended about two inches off the ground. Fluorescent yellow: it does demand your gaze but only to avoid you tripping over itself, it doesn’t want you to fall in the hole or on your face. Why would it? It doesn’t know what it’s like to even have a face.

There are currently four persons on site. In the next few days we are expecting more diggers, consultants and a photographer, some of whom have already made their mark.

****

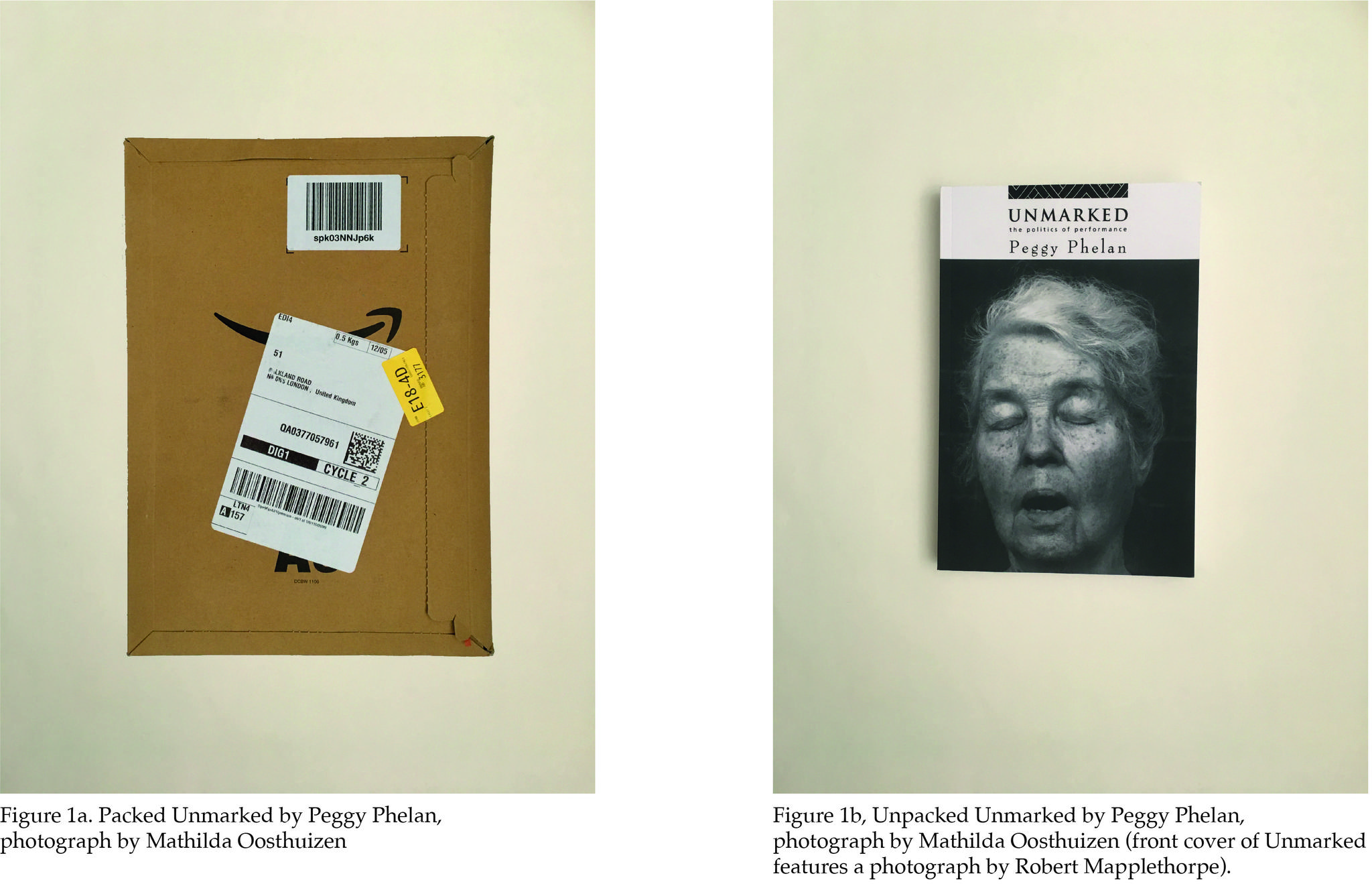

She had been waiting for the package, unsure of how it would arrive. Did the site even have an address? How would they find me? Who would it go to? She was spiralling. It had become a necessity. She had the camera: there wasn’t anything else she needed, technically.

She couldn’t. It was inescapable, staining each thought that entered and left her mind. She had masked her lack of presence so far, but it wouldn’t last for much longer.

––––––––––––––––––

This subject then, that is not visible here, would say something like, ‘[l]acan’s theory of sexual difference ... asserts that it strands woman on a dark continent, outside of language’;[iii] that's why I am here, in the interstices. Still a subject?

Where did the subject come from, this is the question. Gender is brought into the question right at the beginning: ‘the subject has been conceptualized as inherently masculine’[iv] says Susan Hekan, she continues, ‘maintaining the inferior status of women’.[v]

Are there not similarities here between the invisible underrepresented object and the female subject? Should I be reiterating the theories of the formation of the

Another day passed. She was left with no choice but to feign illness. The tent air became heavy despite the cold bite of a February breeze outside. Every nearby noise became a tension of potential relief of her hiding place: the dark space she had found herself, only the other could unzip and peel back. But did she want that? Should she emerge?

All night she had wallowed in her perfumery mental state, drifting in and out of fantasies neither dreams nor thoughts, of different scenarios of its arrival. She last envisioned the package never arriving, that she would be pulled out of her tent in shame, undone, not having taken one photograph and

––––––––––––––––––

Cartesian subject, perhaps Plato or Hegelian phenomenology, forming a unified univocal consciousness through Kant? Probably. Instead I’d like to use this lack to recognise the problem, to alert the reader to the significance of visibility and the potential power of not being seen.

In not supporting a thesis of the object with that of the subject, I instead highlight the impossibility of keeping the subject outside of the object’s existence. To put it another way, the impossibility erupts in the necessity to be recognised in order to oppose. There is a value and a danger in not being recognised, witnessed, acknowledged. When invoked with a deliberate intention; an unpacking process takes place, a possibility for reconfiguring systemic inadequacies. Whereas, when there is a univocal gaze, unknowingly eliminating a difference, instead an eradicating of space takes place, a dismantling of bodies that do not fit. A space for doubles erupts.

So what is a subject? How is it that we have marked ourselves (by ourselves I am meaning those who invited the divide between ‘us’ and ‘them’, constructed what it

asked to leave, or worse, someone would ask her what’s wrong. Too long an answer to give. She stealthily crept from her tent, just after dawn hoping to get some water before anyone saw her.

Cupping her hands, the first gasp of water to purge itself from the pipes since yesterday. Janna’s arm twitched, the icy torrents wetting her sleeve, her ears caught an engine turning near the main gate. Could this be the package? She left the tap, almost running to where a small van was parked.

––––––––––––––––––

means to be called a human and fermented it. And by ‘we’ I was referring to the univocal sovereign sentiment, pasted, planted, superimposed, entombing what is a sense of self) off from everything else that has ‘cast man on the other side of the animals.’[vi]

Assumptive systems that ‘privilege not only the human but a particular kind of (European, masculine … - a carnophallologocentric subject’ [vii] a quote from the aptly named book, Becoming Undone. A discourse which undoes (or hopes to undo) the accrual of power and how it is bestowed. How should one be granted one’s own agency? The necessity for a pass, an entry token, a visible queue that one requires to be allowed in is preposterous.

Out of sight, a trace that is buried. Buried in a visible site on the ‘dark continent’. What if it didn’t amount to only being seen, as Peggy Phelan puts it: ‘what would it take to value the immaterial within a culture structured around the equation “material equals value”’?[viii] That to be buried or not, seen or not, was not a distinguishing factor, but ‘contemporary culture finds a way to name, and thus to arrest and fix, the image of that other'.[ix]And it has already

“Janna Fox?” He exclaimed through the unwound window. He’d seen her. She stretched out her hand prematurely. “You?” She could see it now, he still had it in his grasp, unable to let go. Why wasn’t he giving it to her? Both waiting. “Yes! Yes. Please!” She blurted. He released the package into her possession. Finally, it was in her hands. He shook his head and drove away.

It needed to happen in private, but her tent wasn't the place. Something was about to happen that couldn’t be re-enacted. Once the translucent red tape had been pulled back, that would be it. The rush to her head made it unclear, her breathing was increasing as she looked around the excavation site, searching for where she could privately unpack.

––––––––––––––––––

happened, the image has been fixed and continues to be repeated. Can it be undone?

[i] Judith Butler, Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of ‘Sex’, Routledge Classics (Abingdon, Oxon ; New York, NY: Routledge, 2011), p. 69.

[ii] An archaeological dig site is divided into a grid so the excavation area can be documented; that way each find

can be easily located within the excavation area. To create these grids, stakes and strings are used.

[iii] Joan Copjec, Read My Desire: Lacan against the Historicists (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1995, p.216.

[iv] Susan Hekman, ‘Reconstituting the Subject: Feminism, Modernism, and Postmodernism’, Hypatia, 6.2 (1991, pp.44–63, p.45.

[v] Hekman, p.45.

[vi] E. A. Grosz, Becoming Undone: Darwinian Reflections on Life, Politics, and Art (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011, p.12.

[vii] Grosz, p.14.

[viii] Peggy Phelan, The Unmarked, 4th ed (London: Routledge, 1993), p.5.

[ix] Phelan, p.2.

Mathilda Oosthuizen is currently an MA student in Critical Practice at the RCA; she has had work published in Dream Catcher journal and exhibited at Outpost Gallery. Both sound and text are significant materials in her work – useful due to immateriality and their conflicts and challenges with being seen – offering sites for intrigue, invention and a virtuosic entangling of language and (in)visibility.

You can find out more on her website: mathilda.oosthuizen.com