Pablo Luis Álvarez: 'A Birthday Theory'

This piece of writing forms one part of an email exchange between Pablo Luis Álvarez and Joshua Leon, both PhD students at the Royal College of Art.

Dear Josh,

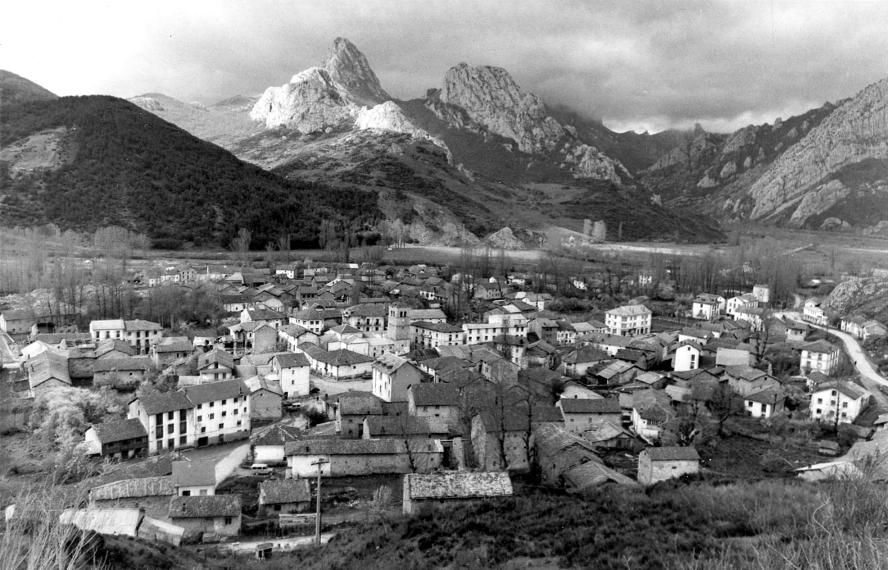

We have talked about my mother’s family, that side of me that smells like incense and dry palm leaves. The other side (my other side), my father’s family, came from nowhere. I, with them, came from nowhere. They came from the mountains, from a place that doesn’t exist any longer. It is a valley where nothing lies, flooded with water: Riaño.

When I was a child, the mere name of Riaño scared me. My grandfather would always talk to me about Riaño so I wouldn’t forget, even though I never got to see the village. The valley was occupied by the Spanish Army in the summer of 1986. I was born in 1991. There was this huge picture of Riaño and its valley at my grandparents’ that covered an entire wall in the front room—Son, keep the name with you and save us.

To the eyes of my maternal family, which actively served Franco and the National Movement, my coming from nowhere was received with suspicion. As the last descendant of a lineage of communists, witches, primary school teachers and shepherds, little could I offer to the National Catholicism that the new democracy had seemingly defeated.

To my father, to my grandparents, to my two great-grandmothers, to my great-uncles and great-aunts, I was a promise for historical justice yet to be delivered. To my mother’s side, on the contrary, I would always come from the enemy. I came from nowhere and thus I was returned, unworthy.

Maybe this is why I always gave so much importance to my birthday. My coming from nowhere gave my birth a mythical origin; I gave myself a mythical origin, as if I had come from the divine—nowhere is the place of the divine, I believe.

There were signs that confirmed the mythical character of my birth. I was born at noon, during the town’s festivities, the Feast of Saints Peter and Paul. A caesarian section was performed on my mother’s womb by her cousin the physician—technically, I was never born. I am nonnatus, that is, not born, taken from the belly of my mother. My father’s brother, who was well-versed in the occult, calculated my astral chart. Neptune and Uranus were in the 5th House, with Mercury in opposition: a serious child, an eccentric personality, ability to read into dreams and omens.

Looking into these things, owning these little facts that meant nothing and everything, allowed me to give myself some space, to have a story other than that of an emissary, always coming from nowhere, moving between two families that could not acknowledge me fully, since I was always sent from the other side.

As a child, my favourite festivities were always those which celebrated the celebration. Commemorative occasions interested me less so, even though there’s something equally commemorative in celebrating the celebration—all celebrations, I think, celebrate with them the last time they have taken place.

Celebrations bring with themselves a celebratory excess that is unswervingly lost; they are always looking back. This is why the liturgical calendar of my childhood was never a circle; it was a spiral, or something like the orbit of Venus as seen from the Earth: a flower.

I think the best example of this looking backward, this liturgical tension about the past that comes with every celebration, is typical of the birthday. One’s first birthday is, ultimately, the day of one’s birth. The day of our birth, our true first birthday, is always marked one year later. As protagonists of our birthday celebrations, we are always very late to the event we are trying to commemorate. It’s slightly tragic: In attending our own birthday party, we render our true birthday irretrievable and unattended.

There is something like a lament in our being late to our birth-day, in the celebration of the last celebration that all festivities commemorate—I celebrate that I was here last year. This is why, in my view, festive tourism, the compulsive attending of parties and festivals, celebrates nothing. But this is a flawed theory of the birthday, since it is incomplete.

I have attached a picture to this email. The lady in the middle is my grandmother, my father’s mother. She was born in a village called Santa María del Páramo (St Mary in the Moor), where people had been so poor that women, emaciated from hunger, could not breastfeed their children and had to feed them raw potatoes that they themselves would first chew so their children could swallow. When she was a little girl, there was no milk in the village. Milk ‘was brought’ in (from somewhere, I always assumed) once a week, and its colour was blue. The idea of a cow that gave blue milk fascinated me as a child, unable to understand how such a thing was possible.

My grandmother moved to Riaño in the early 50s and set up a little academy. She had managed to attend a professional school in León and got a qualification that allowed her to teach children some subjects. I guess the other two girls are her pupils. I’m not sure what year the picture was taken (definitely before 1959, when my father was born), but I do know the exact day: it was September the 4th—her birthday.

Just like the picture manifested itself before me, her grandchild, it is possible that her grandchild alone could have got the date right—definitely, to get the date right, it had to be someone who was from Riaño or who descended from Riaño and its mountains.

It was September the 4th because she was wearing something that I myself would wear on my birthday: a collar or wreath made of sweets, pastries and little beautiful things, possibly some flowers back then. I cannot really translate its name (la cuelga) into English. It would come to mean something like ‘the hanging thing’, ‘the hanging one’, ‘the thing hung’. Your family and friends would lay it upon you on your birthday and you were to wear it, and eat it, on that day. By the laying of the collar, one was attended. By the laying of the collar, one became a festive place. The object transforms you into site and celebration. La cuelga is therefore a powerful device one must not play with: it transforms the bearer into the sovereign of the day—for one day—and into a place for everybody else. By the laying of the collar, my grandmother was both inside and outside; both thing, woman and goddess. It marks the divine origin of everyone’s birth by foregrounding, as Fred Moten would have it, our thingliness, the being-a-thing of our bodies that can make us a site for others to celebrate.

May the objects that you steal attend your birthday, even if you are alone and you have nobody to attend you.

Pablo