Pauline McGonagle: 'Researcher’s Notebook: My First Encounter with Ruth Prawer Jhabvala’

The writer Ruth Prawer Jhabvala (1927-2013) has an extensive oeuvre. This includes 12 novels, one of which was the 1975 Booker Prize-winning Heat and Dust, along with 25 screenplays (22 of which are films), seven volumes of short stories, several plays, and other non-fiction writing. Her early novels, including A Householder (later also a film), Esmond in India and Get Ready for Battle are all set in India, where she spent 30 years. Her later novels, including Nine Lives: Chapters of a Possible Past and Three Continents, along with collections of short stories and publications in The New Yorker, were all written during the remainder of her life in the USA.

Her bequest to the British Library in 2013 mentions her wish to donate ‘all the papers relating to my prose writing to the British Library in London’, ‘in deep gratitude for my life (1939), the wonderful education they gave me, the English language itself, my great love of reading and trying to write, all of which sustained me throughout my life’. The date refers to the year she came to England as a Jewish refugee from Germany. This statement was published in an obituary by Catherine Freeman on The Royal Society of Literature’s website. It also quotes Ruth saying, ‘The films are fun but […] I live in and for the books’.

Most people know about Ruth’s Academy Awards for best screenplay adaptations of E. M Forster’s A Room with a View in 1986, and Howard’s End in 1992, the nomination for Ishiguro’s The Remains of the Day adaptation in 1993, and the BAFTA for Heat and Dust, adapted from her novel, in 1984. My aim was to highlight the significance of her prose works and to attempt to re-insert them into a wider scholarship. Ruth gave a lecture called ‘Disinheritance’ on receipt of the Neil Gunn Fellowship Award in 1979, in which she provided a rare glimpse into her formation as a writer. ‘I feel disinherited from my childhood memories […] really blown about from country to country, culture to culture till I feel-I am-nothing […] As it happens, I like it this way’. I was already aware that Ruth considered 1939 to be the year when her memories began. She wrote about dislocation, setting stories in different places with themes encompassing cultural encounters and immigrant experiences. This lack of rootedness fed into her creativity and imagination.

I was introduced to Deposit 10770, which contained 11 cardboard boxes, on 15 January 2016 in the stacks of the British Library. My expectations of the archive were informed by the plaudits Ruth had received and by my own reading of her novels. My first encounter left me feeling a mixture of awe and fear. Since then I have been examining the collection and listing the boxes’ contents for cataloguing.

The archive contains loose scripts in plastic bags, typed manuscripts of stories with added notes in cardboard folders, hardback notebooks of handwritten stories, and plans for stories and letters from publishers and collaborators, some with original envelopes.

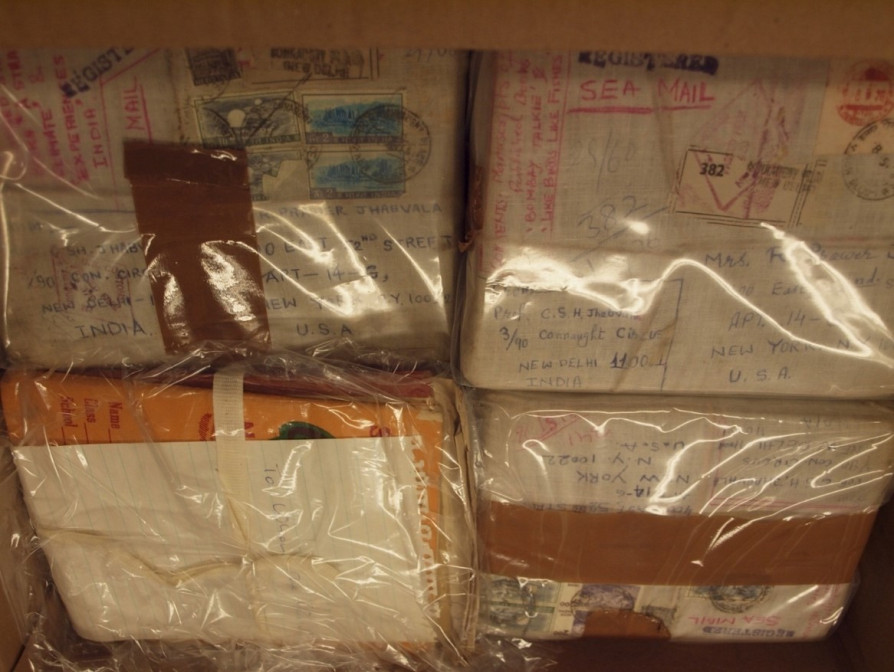

For the symposium, I chose three examples from the boxes to illustrate different levels of engagement. Box #2 is a good example of the stories an object can tell. The packing, dates and American and Indian stamps tell of the box’s global journey. The labels indicate contents relating to the novel To Whom She Will (1955), the film script Bombay Talkie (1969) and the short story collection Like Birds, Like Fishes (1963). The British Museum training I had received on ‘challenging objects’ had not prepared me for how to deal with the tightly packed linen stitched wrapping. At the time of publishing, I am working through the penultimate box and this box is yet to be opened. Designated as the last to be examined, it will be photographed in situ first for the library’s records, and then I will be guided by experienced curators and conservators to unwrap it without damaging its contents. This is also an example of external engagement—reading an archive from the outside inwards. The global journey this box has undertaken echoes the continental shifts of Ruth’s own life and work.

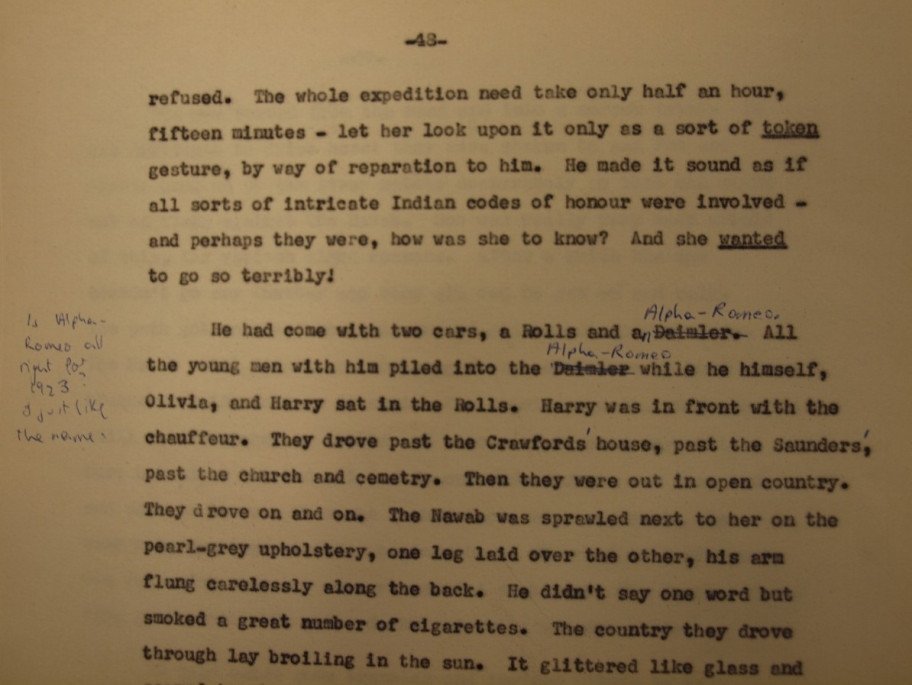

The typed manuscript draft material of her best-known novel Heat and Dust turned up in Box #4. On page 48 of the script an intriguing change from ‘Daimler’ to ‘Alpha Romeo’ (sic) was suggested. The author’s comment in the margin queried whether Alfa Romeo was right for 1923 but gave the reason for the change: ‘I just like the name’. Alfa Romeo survived in the published book. The Nawab protagonist, an Indian prince, also had a Rolls. If a Rolls represented his established status as the ruler of Khatm, where ‘he was fond of entertaining Europeans’, a racier, more modern Alfa Romeo hinted at the unconventional risks the Nawab would take to elope with Olivia. Jhabvala’s writing is always precise and succinct, so the romance inherent in this particular word choice is effective. The character Olivia is the wife of a British government officer posted to India in the 1920s who has an affair with the Nawab. The novel uses analepses so that the unnamed narrator, who is Olivia’s granddaughter, travels to India in the 1970s with Olivia’s letters to unravel the past and encounter India for herself.

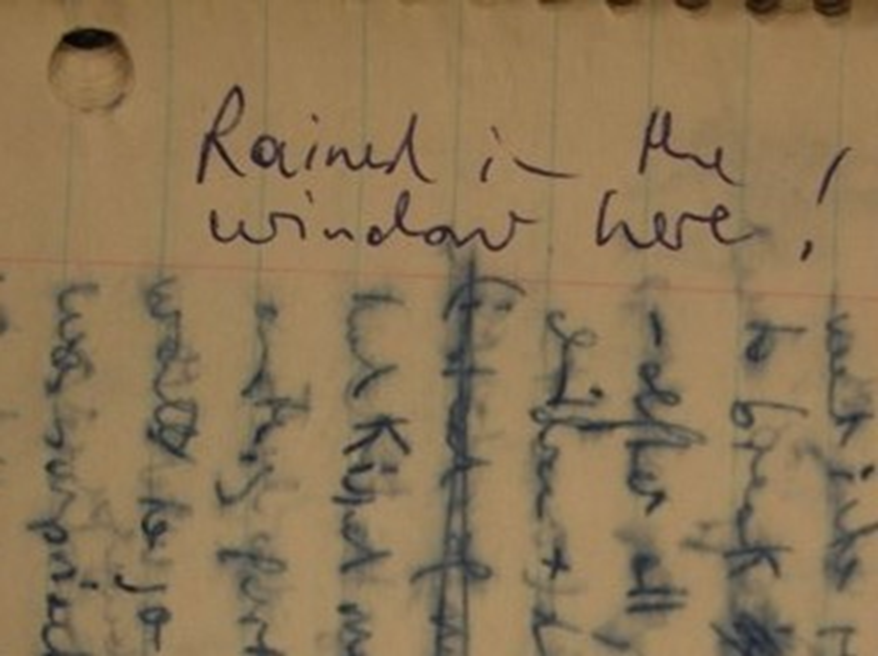

The last example came from a notebook in Box #4, covered in dense handwriting. I was examining it for loose papers when I noticed obscured pages which had once been wet and were now illegible. While resting my eyes, I considered the cause of the damage. Then suddenly, I noticed her handwriting in the margin. The words written in biro were: ‘rained in the window here!’

Her voice spoke to me directly in what felt like a shock encounter of great clarity, which made me question whom she intended to address. I thought about the active part writers play in creating their own archive. I needed to interpret all these material objects carefully while listening to her distinctive voice. Despite my efforts at professional distance, I was now aware that Ruth’s voice and I were engaged on a personal level that I could not ignore.

Pauline McGonagle is a part time PhD student, funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council’s Collaborative Doctoral Award. The project is co-supervised by Rachel Foss, Head of Contemporary Archives and Manuscripts at the British Library and Dr Florian Stadtler from the University of Exeter. This article has been adapted from a paper called ‘First encounters: object, material and voice’ given at the Global Voices in the Archive symposium held at the British Library Conference Centre on 21 March 2016.