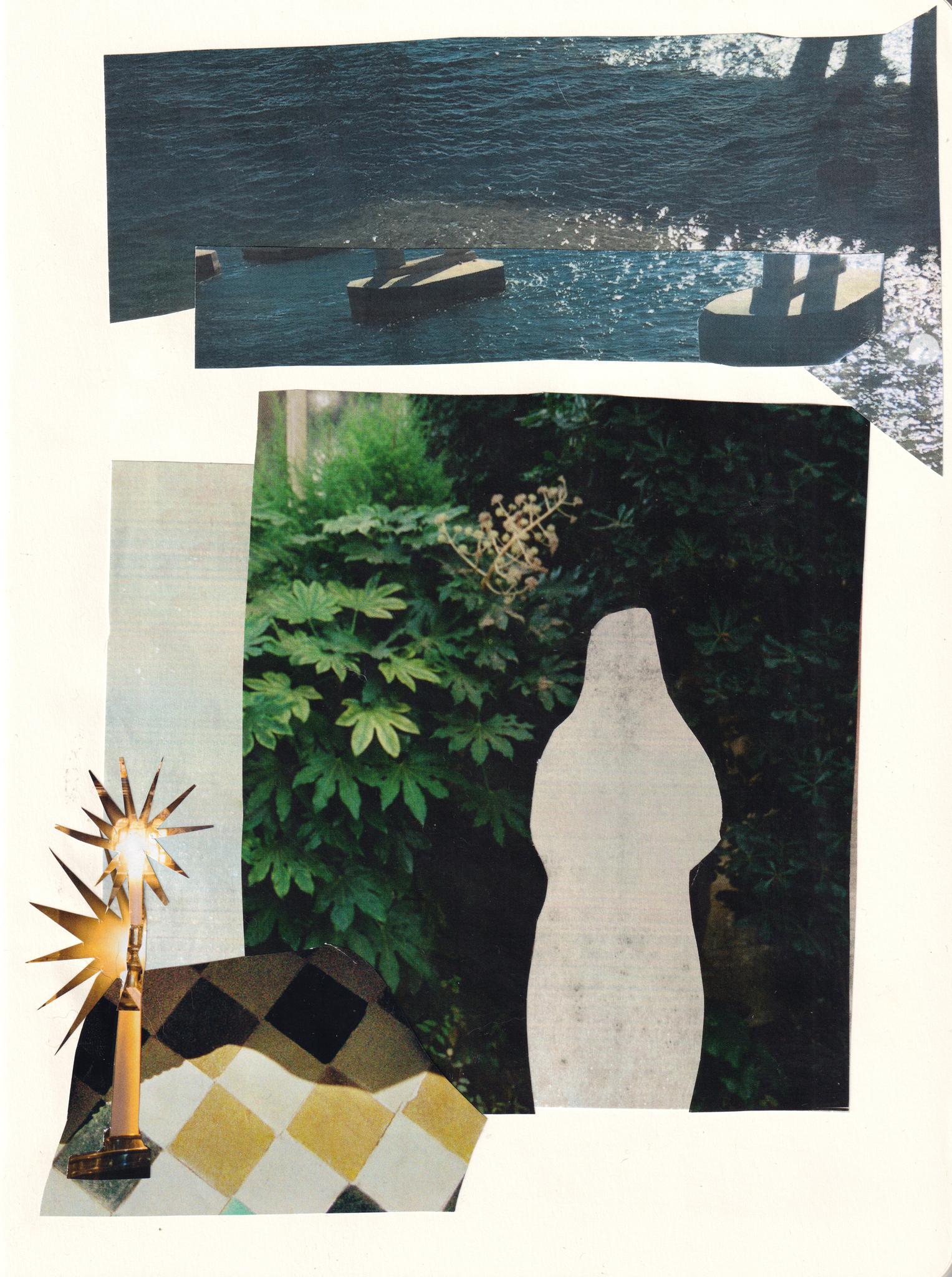

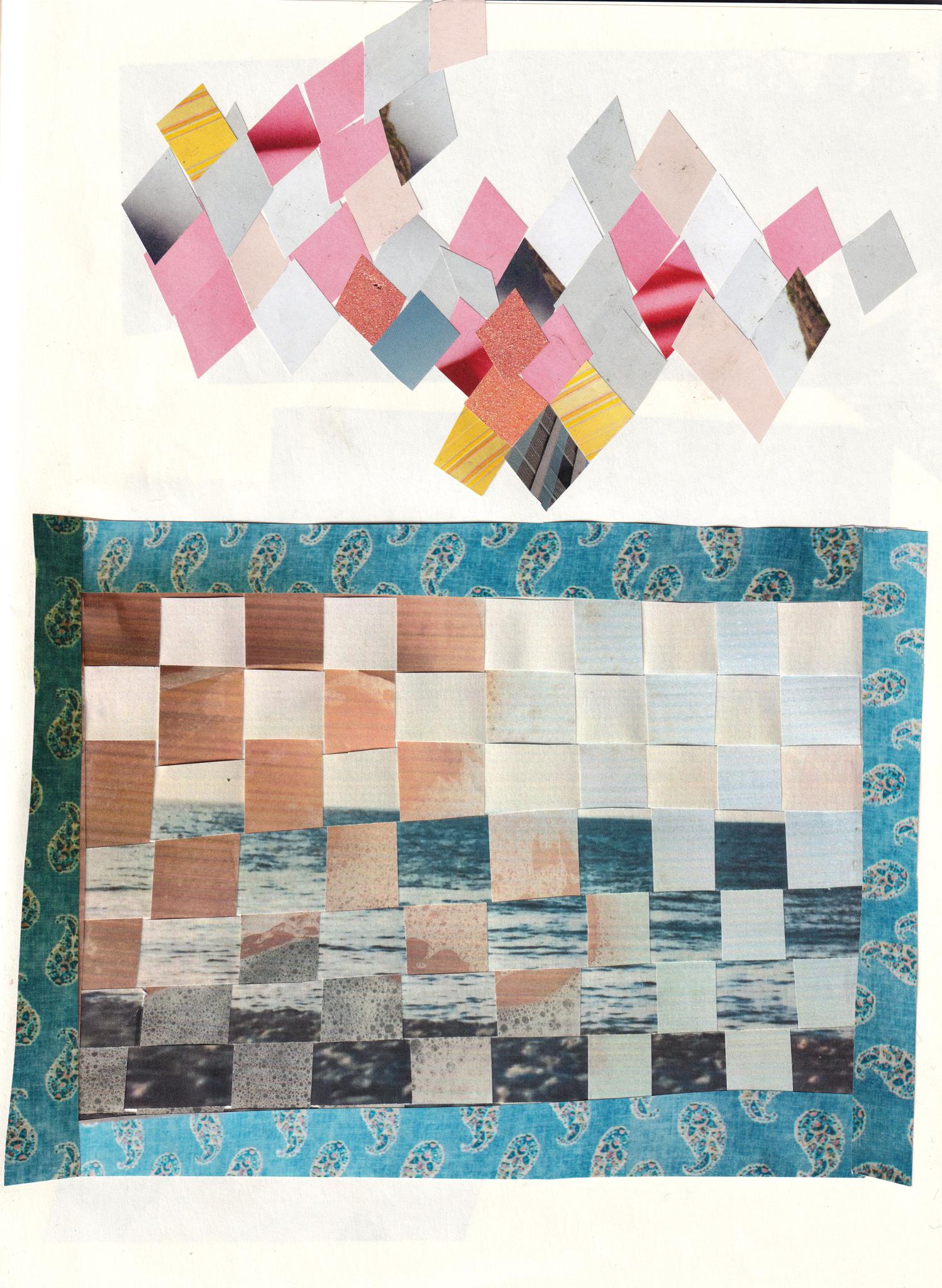

Pema Monaghan: 'bathing zine'

I miss the ocean.

Where I was born and raised, in Noongar boodja (South-West Australia), it was only ever fifteen minutes in the car to the beach. Swimming was the most important thing in the world and a sandy healthiness was expected of all children. Summer days not spent at the beach were passed in chlorinated outdoor swimming pools, laying on your front on poured concrete so hot it would leave you with burns, and eating salt and vinegar chips from the tuck shop. Swimming lessons were mandatory in both primary school and high school. You had to be strong enough and knowledgeable enough to swim through a riptide or, so adult logic went, you’d inevitably drown at some point or another.

My dad used to get up before the sunrise so he could beat everyone else to the beach. He’d swim from one pier to the other, occasionally joined by local equestrians bathing their horses in the green morning light. I liked the beach best on still summer evenings, the water barely rippling as the setting sun cast out dreamy tones of peach and lavender. I loved to be held on the surface of the water, buoyed up by the immense salt levels. It would bring my spirit back down to reconnect with my body.

I don’t live close to the sea anymore, so when I submerge myself now it is usually in the bath.

The tub I remember using as a toddler was a beige rectangle surrounded by glossy 70s’ mustard tiling, built into the side of the bathroom next to a showerbox constructed of a matching yellow glass. My mother would fill it with non-toxic bubble mixture out of a receptacle shaped like a little sailor boy. I would eat the bubbles (I guess that’s why they make them non-toxic).

But Western Australia was perpetually in drought. Every year in school we learned about the importance of controlling our individual water use. Baths were for babies, they were a luxury, like watering your lawn in the summertime. Once we were old enough, it was all showers always. If we wanted to submerge ourselves, we could always go to the beach. My dad, dogmatic about not wasting water, installed a tiny hourglass in our shower. Once the two minutes that it took for the sand to run through the timer elapsed, we had to be out. We’d turn off the taps while washing our hair, even in the winter. If we were clearly abusing our shower time, we’d hear a loud knock on the bathroom door - “that’s long enough, bub”.

(Recently, speaking to dad on video chat, he suddenly broke off our conversation. “Your sibling’s been in the shower for hours,” he said, sighing, and went over to knock on the bathroom door. Then, “Murph, that’s long enough, bub”.)

Later on, renting a room in a small dark unit built for the 1987 America’s Cup, or an asbestos-ridden 1960’s cottage, I’d be in and out of the ancient bathrooms as quickly as possible. The fastenings were always green with rust and leaked out coppery water. And anyway, it made no sense to come in from the sweltering day only to further sweat yourself in a bath. Or in the winter, to come back drenched from a thunderstorm on the way home from university just to spend more time in the wet. Better a short and extremely hot shower.

I do remember one significant bath in Australia. Visiting Melbourne with an ex-boyfriend, we went to stay with a friend who lived in the Dandenong Ranges. The friend picked us up from the airport, and drove us terrifyingly fast up the frosted mountain roads to where he’d been building himself a beautiful house. The friend asked me if I’d like a bath in his new bathroom. He ran it himself, lit the candles, and opened the window wide into the forest. It was raining out there. The water was so hot, and the air so cold, that steam bounded off the surface and out into the night. That was the most transcendent bath of my life, the platonic ideal of baths.

There were also the baths that I had in my imagination, baths in colder countries. Literary baths. Like in Dodie Smith’s I Capture the Castle – Cassandra Mortmain sitting in her portable tub by the fire in the hollow kitchen of her castle, surrounded by dust sheets newly dyed green which hang off tall clothes horses, ill-advisedly feeding chocolate to her dog Heloise and basking. Cassandra staves off the last part of the bath when the water is too cool, which, she says, “can be pretty disillusioning”, by pouring in new hot water from the nearby copper kettle. Cassandra is sitting in this bath when two American men knock on the castle’ kitchen door and change her life forever.

Or film baths, like in Miyazaki’s Spirited Away – the steaming herbal bath Chihiro pours for a river spirit who has sloshed into the bathhouse covered in mud, human waste and rubbish. The spirit is so grateful for Chihiro’s care and efforts to free them of this baggage that they leave her a precious green medicine ball, which she later uses to save the lives of her parents and Haku the dragon.

Now I live in the UK. It’s summer, and it’s hot. Today I had a lukewarm bath because my body was aching after having my first Covid-19 vaccine. I poured in a bubble mixture called Badedas. My boyfriend bought it. It makes your bath bright green, and it supposedly smells like horse chestnut (it’s a nice scent even though I’m not sure what horse chestnut smells like). It’s what his mum always uses in her special baths.

I got big into baths when I moved here. On a winter night, coming home from an evening shift at the garden bar I worked at when I first arrived in the city, I’d be shivering, sticky with old beer, and covered in unidentifiable, muddy streaks. I’d quickly hose off my legs, and then fill the bath with hot water, though only ever half way, guilt-ridden over the waste. Then I’d put my laptop on the closed toilet lid, and put on the most comforting television show I could think of, usually an episode of Doctor Who.

There were unexpected baths. A few years ago, washing my hands during a Swedish kräftskiva party, I drunkenly fell into a tub still full of the herb and lemon marinade in which the crayfish had been soaking. I arose out of the water, bruised, incredibly wet and smelly, but unstoppable. I took off my tights and turtleneck and went back out to dance, spraying others with the droplets of marinade that span off the strands of my long black hair.

Artist Abi Palmer’s literary memoir Sanatorium has attained cult status amongst the chronically ill people I know. Palmer, in her late twenties and living with a complex set of disabilities, spends a month at a thermal bathing rehabilitation centre in Budapest. At the centre, more time is spent in the baths than out of them. Palmer meets people there who make extended visits every year. Other months are spent saving and preparing for their trips. Lives oriented around the chance to bathe.

Back in London, Palmer buys an inflatable bucket, big enough for her to submerge her entire body, and fills it everyday with the hottest water possible, so hot she teeters on the edge of faint. She keeps glasses of water nearby to “bring [her] round”.

Maybe that seems like a punishing routine. But it’s something I do myself. Somewhere in my own mid-twenties my relationship with baths twisted, no longer luxury “self care” but something more medicinal.

I rely on baths as a sort of rest cure band-aid for my chronic illnesses. On bad days, I creep to my little tiled room and run the water hot, hotter, hotter, as hot as I can stand, so that it turns my limbs red like the crayfish in the kräftskiva bath. The shock of the heat sometimes brings me back to myself. I lie still as the water cools, too fast.

Friends give me bottles of bath oils, milks, sachets of herbs, seaweeds, bubbles as gifts. I’ll try anything, but I like salts the most. I believe they make the water feel softer, and sitting on undissolved crystals feels like laying on the sand at the beach (almost).

No single bath has saved my life, or transformed it, like they do for girls in books, but they usually make me feel a little bit better.

When you’re in the bath. Try this:

Open the window, let the air in. Lower the back of your head into the water and close your eyes. You could be anywhere. Baths can take you home.

Pema Monaghan is a Tibetan-Australian writer and journalist from Noongar boodja, now living in London. She has recently written for gal-dem, New Rules: Play during the Pandemic, the Willowherb Review, Ache magazine, and Extra Teeth magazine. Along with the artist Oscar Price, Pema runs Takeaway Press, a small house that publishes collaborations between artists and writers.