Peter Chappell: 'Finding Your Light'

I first came across the phrase “found my light” in a video tweeted by Charli XCX in 2019. She smiles to the camera in hot-pink eyeshadow, bathed in a strip of bright, warm sunlight. The clip was meant to promote her new song with HAIM, but she’s distracted by her face, and revels in the light instead.

Why do we crave a warm glow in images? In the twenty-first century, we think warm sunshine makes us look healthy. It gives a sheen of success: it’s easily achieved on holiday (as archived on Instagram, a platform which algorithmically selects for brightness and intense colour). Constant bright sunlight is California, it’s uncanny commercials with people holding branded drinks and grinning perfect smiles, it’s sunset lamps and ‘golden hour.’

Many people have spent time in parks this year playing at being versions of these people. The overcast spring and summer has made the sun less consistent, and therefore more notable. In the city, the evening sun sinks between the houses and will sometimes bestow its light on the park. In the countryside, shifting clouds affect a similarly fleeting glow-up. In the warm umber of an evening glow (remember early June?), catching “your light” is sometimes the cue for congratulations and selfie-taking.

When we look at a sunset, we appreciate its transient beauty. When the same sunset shines on us, we suddenly become part of its beauty. For a moment, nature, the exotic and the potential of image-making collide on our faces.

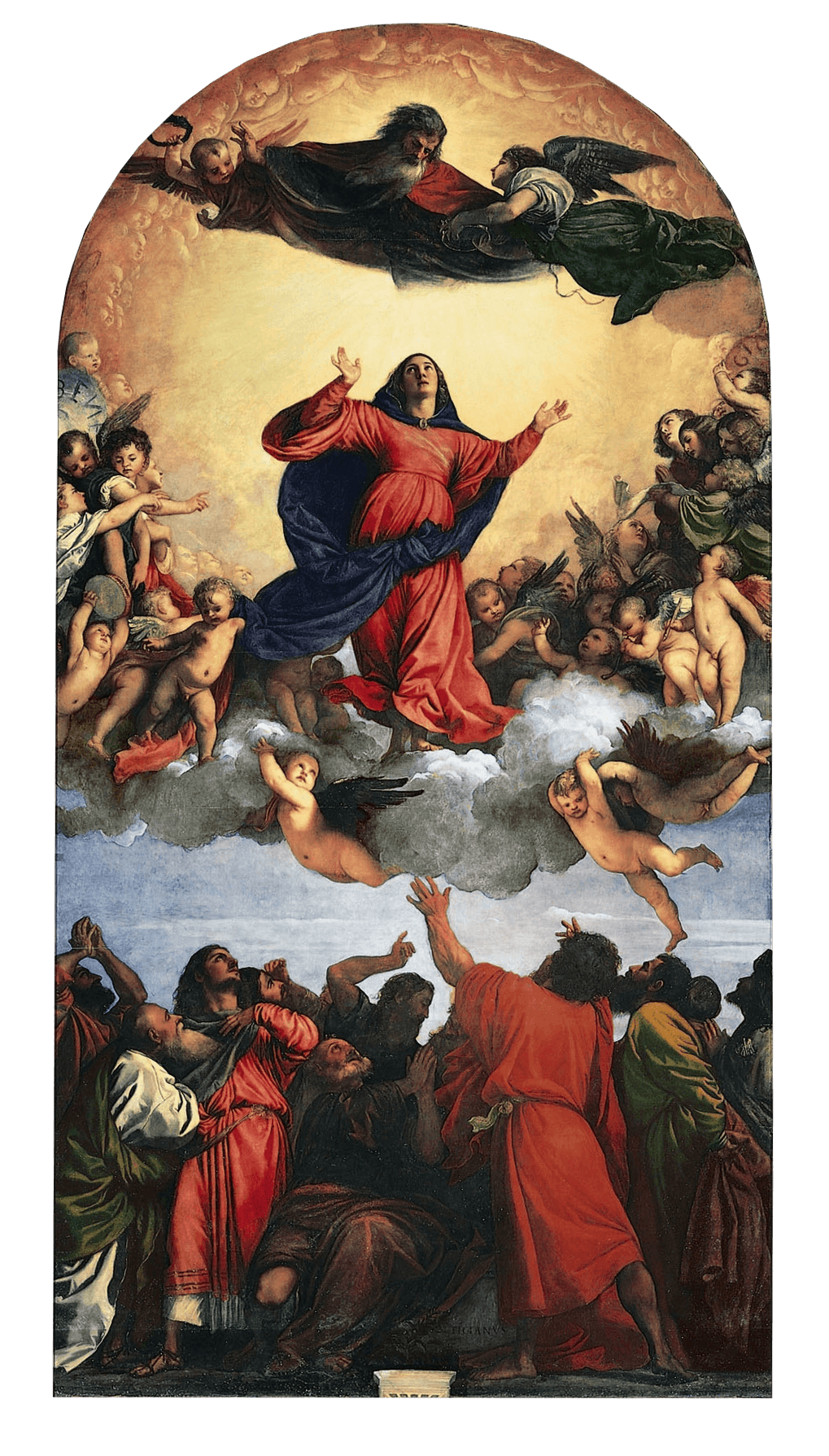

But the glow we try to capture on smartphone cameras has always been a metaphor for artists to draw on to depict happiness, superiority and acceptance. The Assumption of the Virgin (1515 - 18) by Titian is the largest altarpiece in Venice, hung at the back of the Basilica di Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari. It was designed to be surrounded by hundreds of flickering candles. Titian has Mary bathed in the warm light for which his hometown is famous. Conventions established in the Renaissance endure: the stereotype for any deus ex machina is a downwards celestial light to precede the moment of intervention. In an engraving by François Chauveau of a stage design by Giacomo Torelli for Andromède (1650, below), a French verse play, Jupiter arrives to welcome the mortals to heavens, surrounded by a halo of thin sun rays. They fall with a steadiness and insistence which exudes kingly authority and acceptance. But these conventions were never stable or uncontested.

After the Reformation, dramatic rays of light emanating from the white-bearded head of God fell out of fashion. For the seventeenth-century Protestant Dutch, God's light didn’t disappear but was reimagined by Vermeer within a more subtle and domestic environment. In Women with Water Pitcher (1662), milky light streams into the room, rewarding the steady hard work of the woman. Lit from above, the woman is literally highlighted — the exact colour might be different, but the movement of light from on high to those below is the same.

Both Titian and Vermeer present celestial light as all-encompassing. It envelopes their subjects, even if it produces Catholic ecstasy or Protestant meekness. Vermeer and Titian are painting, in part, to explore a very specific moral filter: the purifying nature of the Christian god’s grace. Their light is a metaphor for the total nature of his love and ownership of human souls. It is a kind of light which illuminates and exposes, just as the sun falls on everything with uniformity. Glow-as-divine-power has authoritarian implications: like Vermeer’s servant, God cleans not through consent but through rough and painful scrubbing

Has this power arrangement remained in our modern aesthetics? And if so, how has it been reinterpreted amid our current technological obsession with light?

Light from the sun in many countries is frustratingly unpredictable and you have to be outside to fully catch it. In response, social media companies have invented filters to provide us with an technologically synthesised version. What Titian and Vermeer did over months we can do within seconds. Instagram and Snapchat’s tools have shown us what we value in nature’s “glow”: their filtering options flatten flaws, they smooth our bad skin and moles, they sharpen the contrast between the colour of our eyes and our skin. Like the sun, they brighten and purify us.

These filters serve precisely the same purpose as make-up has done over the centuries, to accentuate features and make the face radiant. Their rise has run in parallel to a make-up aesthetic that has emerged on social media, with roots in old-school drag cosmetics. Elements include very dark, sharp contour under cheeks, "carved out" eyebrows and, above all, heavy highlighter on the cheekbones, brow bones and tip of the nose

There’s a sense of theatricality; James Charles’ bright eyes and primary colours. But that same theatricality is at work in Titian, too: his vision of the assumption is ecstatic, it’s performative, the figures writhe with excitement and drama at what’s happening

Achieving “glow”, or “finding your light”, is a moment for a celebration now just as it was then. In a religious context, it had a moralising, authoritarian edge: you cannot escape God’s light, for better or for worse. The techniques used by Titian and Vermeer — garishness, bright colours, shadows and highlights — have now been democratised and are used every day by anyone with an iPhone and the app. But a power relation is still at play: like God’s sun rays lighting up Mary’s face, the software’s purifying vision is projected onto us. Instead of inducing religious adherence, the projection is designed to be monetised by the owners of the platform. Maybe the reason Charli XCX was so pleased to “find her light” was because she was getting for free from the sun what centuries of artists and now software companies offer for a price: a golden glow and a promise of purity.

Peter Chappell is a writer from London. He publishes an arts newsletter called Bitter Lemon.