Rosa Appignanesi: Salome Salome Salome

Let’s start with a well-known historical tragedy. On April 3rd 1895 at the Old Bailey in London, Oscar Wilde first appeared in court after suing the father of his lover for defamation. Lord Queensbury, enraged at Wilde’s relationship with his son, had left a card at Wilde’s gentlemen’s club calling him a ‘posing sodomite.’ Wilde retaliated with a lawsuit. The only problem was that although the note was incendiary, Wilde had not been discreet in his sexual relationships with men. Queensbury’s lawyers brought out the evidence, conveniently not mentioning his son, Alfred Douglas. The libel case which began with Wilde on the offensive ended with him serving a two year hard-labour sentence at Reading Gaol. During this imprisonment he wrote De Profundis, an anguished essay on the relationship between art and suffering, addressing it to Douglas.

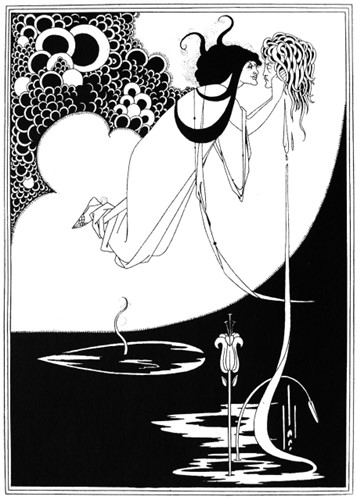

But the tragedy is not over—this is only one iteration of its staging. Near the end of the First World War, a Canadian dancer named Maud Allan was sitting her own defamation trial at the Old Bailey. She was suing a far-right paper, The Vigilante, for their review of her recent play, Oscar Wilde’s Salome (1893). They had headlined the article ‘The Cult of the Clitoris,’ accusing Allan of celebrating Lesbianism, of being a German spy, and of having an affair with Margot Asquith, wife of the former Prime Minister. The star witness in defence of The Vigilante was Alfred Douglas. The man who had once written of ‘the love that dare not speak its name’ now published poems accusing Asquith of being ‘bound with Lesbian fillets.’ Bosie was not called to testify to the validity of claims against Allan—he didn’t know her—but to the perverse moral climate, back in the 1890s, in which Salome had been produced. On a historical level, both Wilde and Allan’s trials are landmark legal cases in the public status of homosexuality in Britain. But they are also tied – and allow me to be ethereal here – repetitively, mimetically—to the recurring figure of Salome. By this I mean Salome not just as a Biblical femme fatale, or as a Decadent muse, or as a queer icon, but rather the sum of these divergent interpretations: Salome as a figure who circulated within both high and popular culture, whose continuing presence serves to symbolise the less than impermeable border separating the imitations of art from the life that it imitates.

a

a

In the Gospel of Mark, Salome dances at the request of her uncle/step-father King Herod. Herod says he will give her anything she wants in exchange. She agrees, and encouraged by her mother Herodias, asks for the head of John the Baptist – a critic of her mother’s illegitimate marriage to Herod. The sensuality of its imagery had long made Salome a popular figure in Christian art, but this reached something of a fever pitch at the turn of the twentieth century. Introduced to the elite world of the Parisian salon in 1891, Wilde would have been met by a gallery of competing Salomes, produced by artists and writers like Gustave Moreau, Stéphane Mallarmé and Gustave Flaubert. Among this party, Wilde was perhaps the first to be interested in telling the dancer from the dance. Lyrical, basically plotless and archaically stylised, Wilde’s Salome is a strange tragedy, an angry tragedy, which reads as a celebration of the kind of passion almost universally decried as monstrous. ‘I am amorous of thy body, Iokanaan! [John the Baptist—Wilde exoticizes by de-anglicising]’, Salome exclaims at regular intervals. Holding his severed head, she screams, ‘thou wouldst not suffer me to kiss thy mouth, Iokanaan. Well! I will kiss it now. I will bite it with my teeth as one bites a ripe fruit.’

Lines like these retain their power to scandalise. Writing in De Profundis, Wilde reflected that he ‘took the drama, the most objective form known to art, and made it as personal a mode of expression as the lyric or the sonnet.’ Salome’s dialogue is similarly positioned from the inside-out, its characters shaping their surroundings through acts of description. ‘How good to see the moon!’ Salome exclaims:

She is like a little piece of money, you would think she was a little silver flower. The moon is cold and chaste. I am sure she is a virgin, she has a virgin's beauty. She has never defiled herself. She has never abandoned herself to men, like the other goddesses.

The play is full of instances where gazing is not a neutral action, but self-consciously constructs its subject. Yet Wilde is drawing on a tradition of imagery which he is simultaneously collapsing by overloading it: the moon here is at once touched and untouched, cheap and priceless, little and abstract. Salome’s description of the moon becomes a pastiche of many contradictory images of femininity, discarded as quickly as deployed by her shifting associations. This is a world in which characters are self-conscious of their metaphors’ relationship to their objects, of art producing the life that surrounds them.

Yet, much like her overloaded description of the moon, Salome had herself become an overloaded signifier by the time of the play’s publication in 1893. The subtleties which for Wilde made Salome ‘as personal a mode of expression as the lyric or the sonnet’ would coexist alongside a rapidly expanding market of Salomes, for all types, across all forms, high and low— from operas to nightclub stripping, oil paintings to cigarette packaging. The fin de siècle Salome courted to maximum effect a combination of sexual subversion with wide commercial appeal: ‘Now the Daring Salome Dance Raged through the World like an Epidemic,’ ran a 1908 headline in The Baltimore Sun. People called it Salomania. Morally, sexually, and commercially, the image of the dancing, orientalist Salome was catching on.

a

a

In the spring of 1918, Maud Allan was approached by the experimental theatre producer Jack Grein to star in his new version of Wilde’s Salome in London. Allan had already been touring her version of the Seven Veils Dance across Europe for ten years; relishing both the provocative censorship laws in Britain and her first chance at a speaking role, she accepted. Controversy was to be expected, but not to the level of national scandal that eventually arose. It was nearing the end of the Great War, and anxieties over national security were being increasingly stoked by an atmosphere of conspiracy and misinformation. One such stoker was Noel Pemberton Billing, MP for Hertford and the founding editor of The Vigilante. Billing, like so many maniacal attention seekers, had been an actor before a politician. He had never stopped performing—his role as an MP was to proselytise the Black Book, a list he alleged was kept by the Kaiser containing the names of 47,000 high ranking British citizens who were also German spies, Catholics, paedophiles, Jews, homosexuals, communists. ‘It is a most catholic miscellany,’ Billing begins ominously, ‘The names of Privy Councillors, youths of the chorus, wives of Cabinet Ministers, dancing girls, even Cabinet Ministers themselves, while diplomats, poets, bankers, editors, newspaper proprietors, members of His Majesty's Household follow each other with no order of precedence.’ In this menagerie of professions, the ‘wives of Cabinet Ministers’ and ‘dancing girls’ stick out—a hint towards the scandal Billing was soon to manufacture using Margot Asquith and Maud Allan.

But what in this period made lesbianism, in particular, a site of hermeneutic obsession for someone like Billing? On one level, the anxiety of interpretation prompted by the war spy is not dissimilar in structure from the interpretative questions prompted by the closeted homosexual: How do you know who you’re talking to? Is someone appearing as they are, or are they merely affecting an imitation? Who—quite literally for Billing—is in your bed? ‘Germany has found that diseased women cause more casualties than bullets,’ he wrote, arguing that Black Book members were maintaining a web of sex workers deliberately spreading STIs to British soldiers. Salome’s repeated representation as a cultural disease, plus the belief that homosexuality itself might very well be spread by publicity and imitation, made Allan’s performance in 1918 an ideal focus for Billing’s conspiratorial propaganda. The headline ‘The Cult of the Clitoris’ itself suggests the dangers of group expansion, centring provocatively on the locus of female sexual pleasure—the clitoris—rather than on the organs of reproductive futurity. In Billing’s account, Allan’s Salome is an example of an undesirable population expanding itself via culture. It goes without saying this is a fascistic logic, but it is worth attending to in so far as it suggests something central to how we speak about the politics of appearance versus reality: about who produces and thus controls the terms of investigation and revelation.

Back at the Old Bailey, in an arc strangely similar to that of Wilde’s trial, Allan’s strategy of suing The Vigilante backfired. Billing, representing himself, filled the courtroom and outside the court with his supporters who cheered and shouted constantly. He was full of pithy remarks; things were ‘lies’ rather than misinformed, and Bosie was even removed for calling the judge a liar. The prosecution pointed out this was all a grift for Billing, drawing on the immediate social interest garnered by anything connected to Wilde, and subsequently warned ‘he must not seek actions in law in order to get an advertisement.’ But the defence of Salome itself was anaemic: Wilde was described by them as a ‘curious perverted genius’ who had proved himself capable of writing ‘clean and amusing’ comedies as well as this ‘very unpleasant tragedy.’ Salome was not lesbian, they argued, but admittedly could be considered ‘sadistic’ in parts. Billing complained he was not able to cross-examine Wilde, long dead, much to the amusement of the gallery.

Eventually, he withdrew his unsubstantiated accusation of a sexual relationship between Allan and Asquith, and the question for the jury became about the Sadism of Salome, whether ‘that was the intention of the play, and then whether, if it were, that was the way in which the actress, Maud Allan, represented it [my emphasis].’ (The Evening Sentinel, 4th June 1918). The legal terms here—searching to uncover the relationship between Wilde’s artistic ‘intention’ and Allan’s ‘representation’— indicate to a modern reader the mechanisms of investigative prejudice here. But they are notably not dissimilar from the commonplace metaphors of enquiry within modern literary criticism, which often searches for definitive links between authorial intention and its representation in imagery or description. The Salome saga, then, in its passage from the courtroom to critical judgement, offers an important material addendum to how we now think through the terms of critique. For Allan, her attempt to reclaim the terms of her artistic expression through challenging The Vigilante was disastrous. Noel Pemberton Billing was found not guilty of defamation by the all-male jury, and the gallery broke into cheers. In Judge Darling’s summing up, he said that her costume’s diamante bra, complete with ruby nipples, ‘can only be described as worse than nothing.’

a

a

Susan Sontag writes in Notes on Camp that ‘Camp sees everything in quotation marks. It is not a lamp but a ‘lamp’: not a woman but a ‘woman.’’ Allan’s bra gives the audience not nothing but ‘nothing.’ The ‘naturalness’ of the naked breast on stage is revealed by costume as an imitation, that is to say, an artistic spectacle anticipated by the desiring gaze of the audience. The bra which both covers and reveals makes a pastiche of this anticipated titillation, at once gesturing towards and then snatching away the sight of her naked body. In this sense, Judge Darling remains correct in his assessment. Allan’s costume is worse than nothing—it is a woman making light of nothing.

In his 1889 essay, The Decay of Lying, Wilde wrote a by-now cliched reversal: ‘Life imitates art far more than Art imitates life.’ Our perception of so-called life is shaped by artistic impression more than we allow, he argues, in a style which playfully reverses the dominant aesthetic principles of his era. To prove the point, Wilde goes on to make a distinction between ‘looking’ and ‘seeing.’ To ‘look’ is simply to note something, he says, but to ‘see’ it grants the object a form of aesthetic existence, animation: ‘Where, if not from the Impressionists, do we get those wonderful brown fogs that come creeping down our streets?’ ‘Seeing’ the fog makes it creep, makes it wonderful; ‘then, and only then, does it come into existence.’ Life doesn’t just imitate art in this account but exists by it. The question becomes—and Wilde is more than aware of the paradox—how can the artist make art if their subject hasn’t yet ‘come into existence’ by them making it? And how does someone switch on the ability to ‘see’ rather than ‘look?’ Wilde is continually indicating towards an origin of creative impulse that he knows cannot be substantiated. The question here of whether art or life is the imitation is deliberately unbalanced, but that’s exactly the point, undercutting the fallacy (and fantasy) of ‘getting to the heart’ ‘lifting the veil’, of ‘discovering origin’.

In this sense, Wilde’s aesthetic philosophy bears a relationship to the painterly technique of mise en abyme: the placement of a copy of an image within the image itself, creating an infinitely self-referential loop. Brought into a forced dialogue with the truth-seeking, and truth-making, apparatuses that were used against him and Maud Allan in the legal sphere, Wilde’s aesthetic principles resonate with a more urgent political purpose than is commonly attributed to them. If we consider Salome as a play not only staged in traditional theatres (many of which weren’t legitimate) but also as staged repeatedly in the courtroom, it opens ways of reading Wilde which does not foreclose the ambiguous politics of imitation that his work articulates. What, I wonder, would it look like for more essays to take Wilde at his word, not merely to pay lip service to his destabilisation of the Art/Life binary, but to follow it to the letter? And, in doing so, ‘to show,’ as he would write in De Profundis, ‘that false and true are merely forms of intellectual existence’?

Rosa Appignanesi is a DPhil candidate at Oxford, researching late nineteenth-century clinical psychology in literary criticism. She lives in London.